As profound as it has proven to be over the years, human life remains far from realizing all its potential. This piece of knowledge is what nudges us to keep pursuing meaningful improvements within each and every area, but like we know, that is way easier said than done. Hence, to make the said process a little more guided, human beings have constructed certain avenues along the way. While all these avenues, in turn, boast an effective edge under some capacity or the other, they barely reach the level of technology. If we take a second to unpack technology’s journey so far, we’ll see how one of the biggest reasons behind its success is the fact that it hasn’t stuck to any particular template. This would allow the creation to make some sizeable noise across different frontiers, including our global healthcare sector. Now, technology linking up healthcare did feel like a big deal from the start, but very few people were able to anticipate the real scale of it, and when we talk about the real scale here, we are talking about an overhaul. Such a dynamic eventually reshaped the way we used to look at healthcare. In fact, these alternations around our perception will keep on coming, with MIT’s latest development now adding another big wrinkle to it.

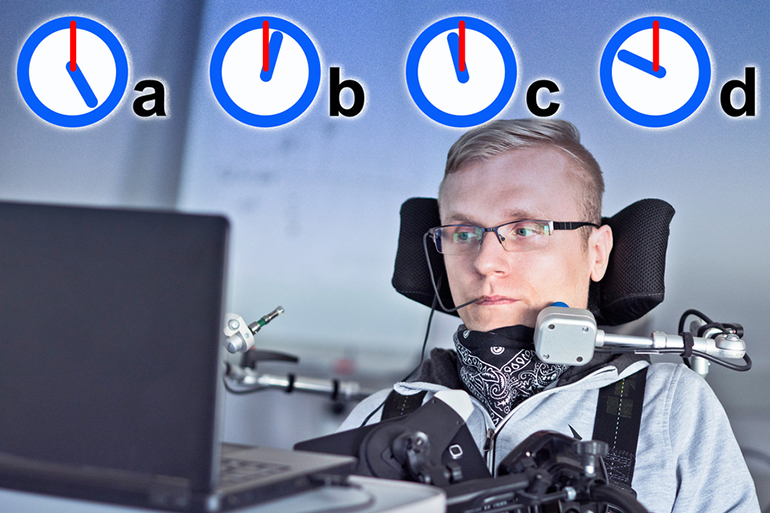

The researching team at MIT has successfully developed a new text selection interface, which is designed to simplify the typing process for motor impaired individuals. The new interface, named as Nomon, ensures that the patient isn’t required to go through every possible letter before they get to what they want. Instead, it predicts the most likely letters a user will choose next, therefore making the selection a lot quicker. Up until now, people with motor impairment complications had no option but to use a grid formation setup where the system literally runs through each letter in sequence. As far as selection goes, the patients would be told to flick a switch or blink their eyes for picking the word. However, according to Nomon’s take, these patients will now have an active clock beside each letter. Assuming the user has located their letter, they only have to wait till the minute hand on its clock has moved past noon before giving the signal. The algorithms powering this technology have also shown a tendency to learn users’ personal traits, thus resulting in a greater experience over time.

“So far, the feedback from motor-impaired users has been invaluable to us; we’re very grateful to the motor-impaired user who commented on our initial interface and the separate motor-impaired user who participated in our study.” said Tamara Broderick, a researcher involved in the study. “We’re currently extending our study to work with a bigger and more diverse group of our target population.”